Enter The Dragon: The FDI Fire

4th June 2025

“Enter the dragon—with both strategic caution and bold opportunity.”

Introduction

In recent months, India has quietly but decisively recalibrated its approach toward foreign direct investment (FDI), especially from its northern neighbor. After years of heightened scrutiny—borne largely out of geopolitical tensions and the COVID-era clampdown on opportunistic acquisitions—New Delhi is now easing the approval process for Chinese investors. This policy pivot comes at a critical juncture: India’s overall investment climate remains beset by challenges, from muted domestic capital formation to tepid private-sector project announcements. And yet, as China’s outbound FDI (OFDI) engine continues to seek alternative destinations, India stands poised to capture at least a slice of that capital.

We examine the broader contours of India’s FDI landscape, the underlying weaknesses that have driven some domestic firms offshore, and the emerging calculus behind China’s intensified interest in investing in India. In doing so, it asks: Can India turn the “China challenge” into a genuine opportunity for sustained economic growth, or are there structural obstacles—both at home and in Sino-Indian relations—that may blunt the impact of this latest policy shift?

I. India’s FDI Environment

1.1. Macroeconomic Context

Over the past decade, India has made remarkable strides in attracting FDI. Under successive administrations, reforms such as the abolition of retrospective taxation, liberalization of sectoral caps, and a swifter single-window clearance system helped channel roughly $80–$100 billions of annual inflows by the end of FY23. These investments spanned manufacturing (electronics, automobiles), services (IT/ITES, financial services), and infrastructure (ports, highways, renewable energy).

Yet beneath these headline numbers lies a more nuanced picture. Gross Fixed Capital Formation (GFCF)—the share of investment in capital goods relative to GDP—has stagnated. After hovering around 17–18 percent of GDP pre-2019, GFCF dipped to single digits during the pandemic and has since struggled to recover. Banks are still grappling with nonperforming loans in certain sectors, and private corporate balance sheets remain cautious about large greenfield expansions. This domestic caution has, in turn, led many Indian firms to seek growth overseas, driving a record $70 billion in outward FDI in FY25.

1.2. Domestic Capital Flight and Outbound FDI

The recent surge in OFDI—an almost 50 percent year-on-year jump compared to FY24—reflects a dual reality. On the one hand, global players from India (Larsen & Toubro, Tata Steel, Infosys, Wipro, JSW, and others) are acquiring businesses abroad to gain technology, distribution networks, and diversification away from a still-fragile domestic demand. On the other hand, domestic investment opportunities have failed to match the returns and scale that these conglomerates seek.

Destination Profile: Traditionally, India’s OFDI was heavily skewed toward “traditional” tax-friendly jurisdictions—Singapore (24 percent of FY25 outflows), Mauritius (15 percent), and the U.S. (15 percent). These hubs allowed Indian multinationals to channel large sums into acquisitions, joint ventures, and “brownfield” expansions across manufacturing, pharmaceuticals, and software services.

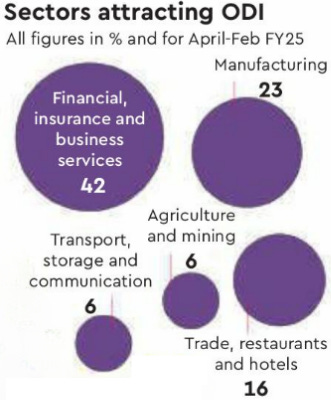

Sectoral Spread: Nearly 42 percent of outbound investments in FY25 flowed into financial, insurance, and business services—many of them acquisitions of global consultants or fintech startups. Manufacturing (23 percent) and agribusiness/retail-communication (16 percent) also attracted significant Indian capital, as firms sought either cost arbitrage or access to regional distribution networks.

While a healthy OFDI story speaks to India’s maturing corporates, it also exposes a relative weakness at home: domestic greenfield capex remains muted. In FY25, private-sector project announcements shrank by nearly one-third compared to FY24, even as India declared grand infrastructure targets under the National Infrastructure Pipeline (NIP). If Indian corporates can’t find attractive opportunities at home, why should foreign multinationals?

II. The Chinese Outbound FDI Conundrum

2.1. China’s OFDI Trajectory and Rationale

Over the last decade and a half, China has solidified its position as one of the world’s leading sources of outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI). According to MOFCOM and SAFE data, the 2023 OFDI flow reached US$177.29 billion, accounting for 11.4 percent of global OFDI—placing China among the top three countries for the twelfth consecutive year. Although 2024 saw a slight dip to US$162.78 billion (an 11.3 percent y-o-y increase in RMB terms but a 10.1 percent y-o-y decline in dollar terms), this still represents remarkable scale. By year-end 2023, China’s cumulative OFDI stock stood at US$2.96 trillion, maintaining its top‐three ranking for seven consecutive years.

Key Drivers of China’s OFDI

Market Diversification

As domestic growth has decelerated—falling below 5 percent by 2023—Chinese firms have been compelled to seek higher‐growth markets abroad. Trade frictions with the United States and the European Union (escalating sharply in 2018 and beyond) accelerated this pivot. OFDI flows into North America, Southeast Asia, and parts of Europe have allowed Chinese conglomerates to access new consumer bases for electronics, machinery, and digital services.

Securing Strategic Resources

China’s industrial sector remains voracious in its demand for oil, natural gas, critical minerals, and agricultural commodities. In 2024, despite broader OFDI moderation, Chinese enterprises invested US$143.85 billion in non‐financial direct investments across 151 countries and regions—a 10.5 percent y-o-y rise. Much of that capital targeted resource‐rich regions (Africa, Latin America, and Central Asia) to lock in long‐term supply contracts for copper, lithium, and rare earths.

By the first quarter of 2025, China’s total OFDI rebounded to US$40.9 billion (a 6.2 percent y-o-y rise), of which US$35.68 billion was non‐financial OFDI—up 4.4 percent year‐on‐year. This uptick underscores Chinese firms’ urgent need to diversify both markets and resource access amid slowing domestic demand.

Source: MOFCOM, China

2.2. Why Chinese Investors Are Eyeing India

Diversification of Manufacturing Base

After COVID lockdowns exposed vulnerabilities in overdependence on Chinese manufacturing, global brands (from electronics to textiles) have begun exploring alternative hubs. India’s Production Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes in electronics, pharmaceuticals, and automobiles have sweetened the pot. Chinese firms—both large conglomerates and smaller component makers—now see India not only as an export platform but also as a domestic demand engine.

Tech and Digital Services

China’s tech giants have amassed scale in fintech, e-commerce, AI, and telecom equipment. While regulatory pushback in the U.S. and Europe has constrained Chinese tech’s overseas forays, India—with its burgeoning digital adoption (over 700 million internet users) and growing fintech penetration (Unified Payments Interface, digital lending platforms, etc.)—offers a fertile testbed. WeChat-like “super-apps,” advanced fintech backends, and AI-driven solutions developed in China could find a second wind in India.

Consumer and Retail

As India’s middle class expands toward 600 million by 2030, demand for branded goods, smartphones, and consumer electronics is surging. Xiaomi, Vivo, and Oppo—already well-entrenched in India’s smartphone market—are seeking to vertically integrate and move up the value chain (e.g., local component manufacturing, R&D centers). Similarly, Sinopharm or Tong Ren Tang might envision launching health supplements or traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) chains across Indian cities.

Strategic Realignment under Geopolitical Tensions

Since the border clashes of 2020 and the subsequent diplomatic standoff, the Indian government had effectively choked large-scale Chinese acquisitions by enforcing a revised liberalized FDI policy that funneled all proposals from “border-sharing” nations (chiefly China) into the inter-ministerial committee (IMC) gauntlet. But as U.S.–China tensions deepen, Beijing is keen to keep investment channels open, even if at a reduced scale. For India, too, diversification of capital sources becomes crucial, especially if U.S. or European capital flows wane in the event of a global slowdown.

III. Policy Pivot in New Delhi: Easing the Path

3.1. Press Note 3 and Its Unwinding

In April 2020, the Indian government introduced “Press Note 3,” mandating that FDI proposals from countries sharing land borders with India—chiefly China—undergo approval by an Inter-Ministerial Committee chaired by the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade (DPIIT). The move, ostensibly aimed at preventing “opportunistic takeovers” during the stock market crash, effectively throttled most brownfield (acquisition-based) investments from China. At the time, Beijing’s OFDI was at an inflection point, and Indian policymakers sensed an opening to protect domestic champions in sectors such as consumer electronics, telecom equipment, and chemicals.

Over the next three years, however, this blanket scrutiny deterred not only large-scale Chinese acquisitions but also smaller greenfield joint ventures (JVs) that could have brought technology, skills, and employment to India. Many Chinese firms simply parked proposals or diverted them to other markets like Vietnam, Indonesia, and Thailand. By late 2023, India realized it risked missing out on manufacturing relocation, especially in strategic sectors such as batteries, renewable energy, and electronics components.

3.2. Streamlined Approvals and Faster Clearances

Beginning in mid-2024, the Economic Survey for FY23–24 and subsequent cabinet deliberations signaled a pragmatic shift. The key elements of this pivot include:

Regular IMC Meetings & Timelines: The IMC now meets at least twice a month, with a clear 45-day timeline to process proposals. In effect, Chinese firms know that a JV or greenfield plant proposal will not languish indefinitely.

Transparent Criteria: Rather than an opaque “national security” catch-all, the revised guidelines spell out sectoral sensitivities (defense, telecommunications, space-related technologies). Investments outside these red-flag sectors—say, in renewable energy equipment, electronics components, or data-centers—can expect faster clearance.

Broadening the ‘National Interest’ Lens: A new clause acknowledges that technology transfer, skill development, and employment generation can themselves count as “national interest,” thus allowing authorities to look beyond purely protective instincts. For example, a Chinese firm setting up an advanced battery gigafactory—leveraging its supply-chain efficiencies—can be justified as buttressing India’s energy-transition goals.

Periodic Review & Real-Time Monitoring: The entire clearance process is now overseen by the Cabinet Secretary’s office, which issues “Press Notes” or “Notices” only when there are serious competition, security, or data-privacy concerns. Otherwise, proposals sail through.

IV. Sectoral Implications and Strategic Trade-Offs

4.1. Electronics & Consumer Durables

India’s electronics imports ballooned to $80 billion in FY24, making it one of the world’s largest importers of smartphones, consumer electronics, and home appliances. Local manufacturing under PLI schemes—though promising—has yet to close the gap between domestic demand and production. Chinese firms with proven “scale-to-cost” advantages could bridge this divide rapidly: setting up local component plants, forging JVs with Indian OEMs, or opening design centers.

Opportunity: Domestic suppliers (PCB makers, consumer durable assemblers) gain access to capital, technical know-how, and off-taker commitments.

Risk: A sudden surge in Chinese-backed capacity can squeeze out smaller local assemblers if government procurement guidelines don’t mandate local value addition or climate/sustainability norms (e.g., e-waste recycling standards).

4.2. Renewable Energy & Green Tech

Given India’s target of 500 GW of non-fossil energy by 2030, the renewable-energy sector has become a focal point for global investors. Chinese solar-module giants (Longi, JA Solar, Jinko Solar) once cornered nearly 80 percent of India’s solar imports. But with “import duties” on solar cells/modules as high as 40 percent, localized manufacturing (with either Indian capital or joint ventures) remains the government’s goal. Easing FDI rules can catalyze partnerships where Chinese firms invest in new solar-panel factories, battery-energy storage systems (BESS), or wind-turbine blade manufacturing—provided they comply with domestic content rules.

Opportunity: India benefits from lower installation costs, technology sharing, and accelerated scale, helping meet transitional climate commitments.

Risk: Oversaturation of Chinese capacity might erode profitability for Indian developers and hamper indigenous innovation (e.g., homegrown thin-film tech).

4.3. Data Centers, Digital Infrastructure & Telecom

India’s data-center capacity has grown rapidly—driven by hyperscalers (Google, Amazon, Microsoft), homegrown cloud providers (Tata, Reliance, Adani), and a proliferating digital economy. Yet, a shortage of Tier-III/IV facilities and high real-estate costs keep prices elevated. Chinese telecom-equipment makers (Huawei, ZTE) have long battled bans and restricted access. But collaborations with Indian system integrators—now possible under the eased FDI regime—could help build next-generation 5G/6G infrastructure and hyperscale data centers. Similarly, Chinese content-delivery networks (CDNs), cybersecurity firms, and AI startups could find new markets in India’s $150 billion digital economy.

Opportunity: Upgrades in digital infrastructure, reduced latency, and lower user costs.

Risk: Data-privacy and national-security concerns remain sensitive. Any Chinese investment in cloud or network layers will face stiff regulatory oversight, potentially leading to delays or forced divestments.

V. The Strategic Balance: Opportunity vs. Vulnerability

India’s recalibrated FDI stance toward China comes with nuanced imperatives—but also inherent contradictions:

Capital Scarcity vs. Security

India needs large pools of capital (especially for infrastructure, clean energy, semiconductors). Chinese conglomerates have billions at their disposal, often funneled through “convertible bonds,” “back-ended payables,” or private-equity vehicles. Against a backdrop of slow domestic credit growth, Chinese FDI can shore up critical capex.

But unfettered capital inflows from Chinese entities could deepen local supply-chain dependencies. The COVID era taught India that external shocks (e.g., supply disruptions, border closures) can cascade into domestic crises if manufacturing ecosystems are over-concentrated in “enemy capital.”

Economic Growth vs. Job Creation

Greenfield Chinese investments in manufacturing can generate thousands of direct and indirect jobs—rare in a post-pandemic economy facing sky-high youth unemployment.

Conversely, if Chinese firms primarily operate capital-intensive, automated factories, the multiplier effect on local employment may be muted. The value-chain (logistics, packaging, branding) might still be dominated by Chinese parent companies, limiting Indian vendors’ share.

Technology Transfer vs. Tech Dependence

Chinese semiconductor-assembly/test facilities (SATS) or lithium-ion battery pack plants could accelerate India’s technological learning curve.

Yet, core IP—semiconductor design software, cathode/anode material patents, advanced battery-management systems—may remain controlled by Chinese parent boards. In the long-run, India could become a “low end” manufacturing hub, while R&D remains captive to foreign firms.

Diplomacy and Geopolitics

By welcoming Chinese FDI, India signals to Washington and Brussels that its “strategic autonomy” isn’t an anti-China crusade. Instead, India seeks to balance ties with both Beijing and Washington.

But China’s own foreign policy playbook includes “Influence via Investment.” Beijing often couples FDI with strategic partnerships in defense, infrastructure, or resource access. New Delhi must carefully guard against investments that compromise border security or grant veto rights in critical supply chains (e.g., rare-earth processing units near contested regions).

VI. Conclusion: A Pragmatic Path Forward

India’s newfound willingness to “welcome the dragon” with open arms—or at least a more efficient visa and capital-flow channel—marks a departure from the containment ethos of the immediate post-2020 period. In a global context where capital is fleeing high-cost, low-growth environments, Beijing is eager to reinvigorate its OFDI engine. India, in turn, must balance its acute need for capital, technology, and jobs against the specter of strategic dependence, market domination, and data-sovereignty risks.

The choice, ultimately, is not binary. India can—and should—engage selectively with Chinese firms willing to commit to long-term, mutually beneficial partnerships. But it must do so with eyes wide open: segmenting industries into those where “China’s involvement” delivers game-changing advantages (e.g., building gigafactories for batteries) versus those where it poses an unacceptable risk to national security or domestic MSME viability (e.g., telecom-core equipment, semiconductor-design IP).

Moreover, India’s broader FDI environment demands parallel reforms: reviving private corporate capex, improving ease of doing business at the state level, reducing intrusion in land acquisition, and bolstering credit flows into infrastructure. Only then can India juxtapose incoming Chinese capital with a more vibrant domestic ecosystem—ensuring that foreign investment augments Indian value chains rather than supplants them.

As China—slowly—realizes that “zero-sum” competition in the global export arena is giving way to “multi-polar” manufacturing networks, Indian policymakers have a narrow window to position the country as the most compelling “China +1” destination. Ultimately, it is the quality of India’s reforms, the clarity of its regulatory regime, and the resilience of its domestic supply chains that will determine whether the incoming tide of Chinese FDI lifts all boats—or risks capsizing domestic champions.

Disclaimer

All information is sourced from publicly available data, and while every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the information provided in these notes from the management meeting, Ayush Agarwal Research cannot guarantee that the information is complete or free from errors.

I, Ayush Agrawal, am registered with SEBI as an Individual Research Analyst under the registration number INH000013013, effective from September 14, 2023.

I offer paid research services to my clients based on this certification. Opinions expressed otherwise regarding specific securities are not investment advice and shall not be treated as recommendations. Neither I nor my associates/ employees shall not be liable for any losses incurred based on such opinions.

All matter displayed in this content is purely for Illustrative, Knowledge and Informational purpose and shall not be treated as advice or opinion of any kind.

The content presented should not be construed as investment advice unless explicitly stated in a client-specific research report. I or my employees/associates shall not be held liable/responsible in any manner whatsoever for any losses the readers may incur due to acting upon this content.

All information is taken from publicly available sources and data. I make no warranties or guarantees regarding the accuracy, completeness, or timeliness of the information provided, including data such as news, prices, and analysis. In no event shall I be liable to any person for any decision made or action taken in reliance upon the information provided by me.

We cannot guarantee the completeness or reliability of the information presented. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research and consult with a professional advisor before making any investment decisions.